How many times have we heard that we are ‘living in unprecedented times’ to sum up our experiences living in a ‘COVID-19’ world? How has our world been changed? What can we learn from our past?

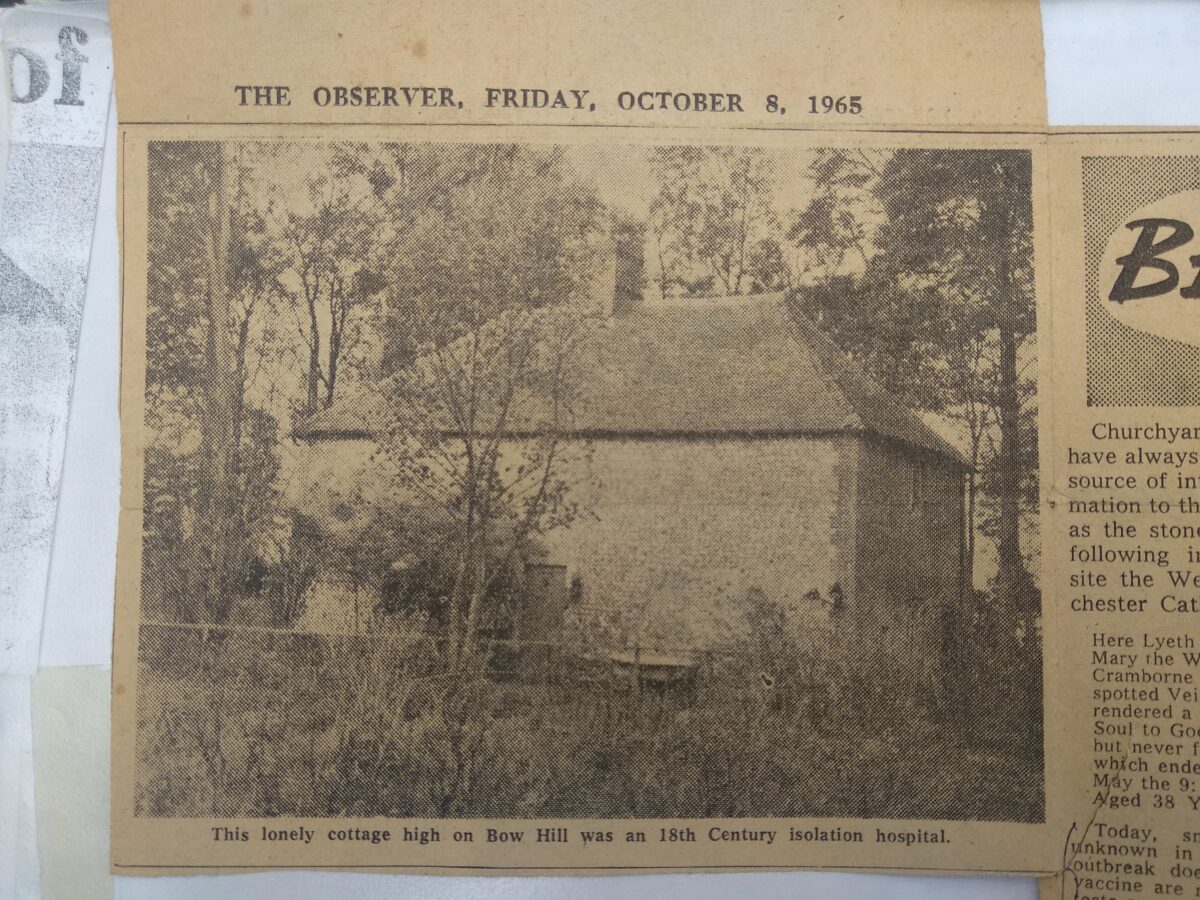

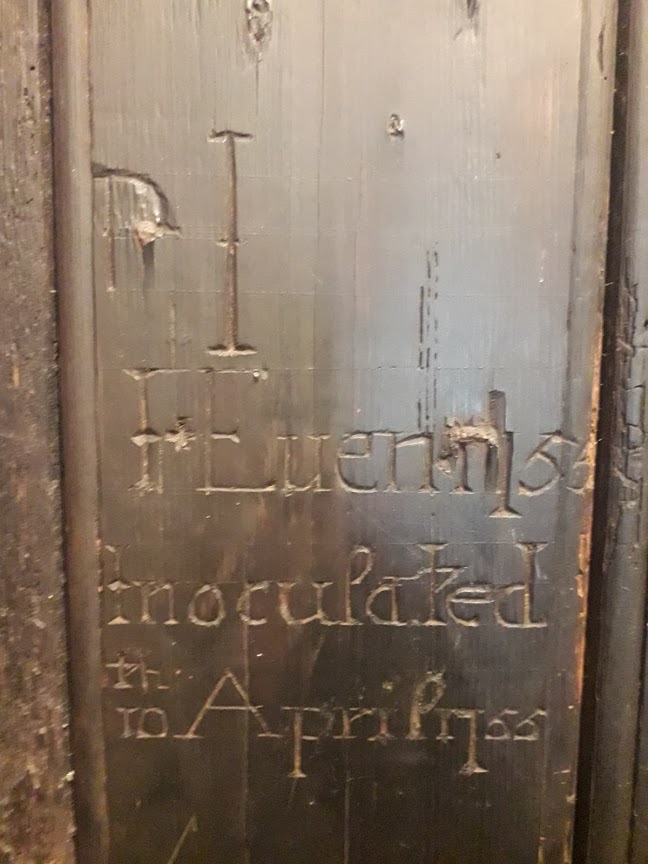

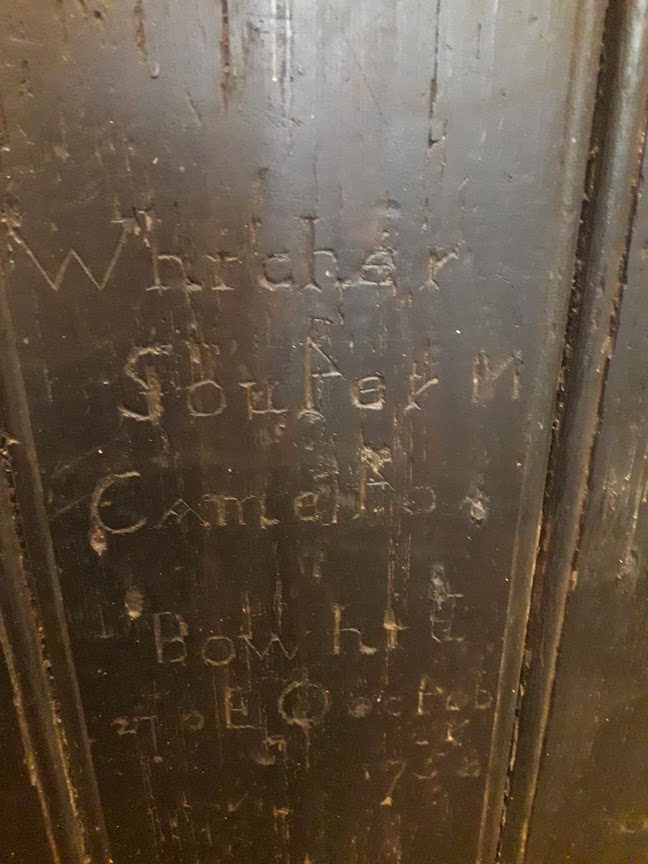

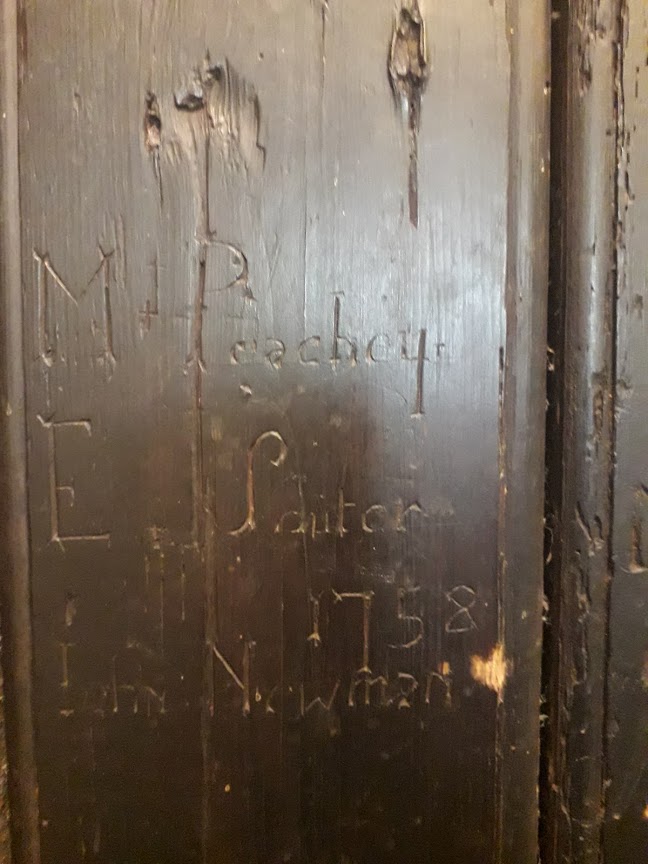

For our 2020 summer holiday during COVID-19 pandemic, we stayed at Black Bush House – an eighteenth century ‘Pest house’ used to innoculate and isolate smallpox, the cause of pandemics and countless epidemics across the world from modern times into pre-history. Doors in the house had names and dates of inoculations carved in to them – happily research by BBC House Detectives, broadcast 23rd October 1998 discovered records to prove that all 19 people with names carved survived long after their inoculation.

Smallpox has easily killed more people than all wars put together. Even after a reliable vaccination was available, smallpox is estimated to have killed up to 300 million people in the 20th century alone. Two hundred years earlier In the eighteenth century, our holiday home was one of the early ‘Pest Houses’ where experimental variolation inoculation was being practiced to protect people from the worst of the disease.

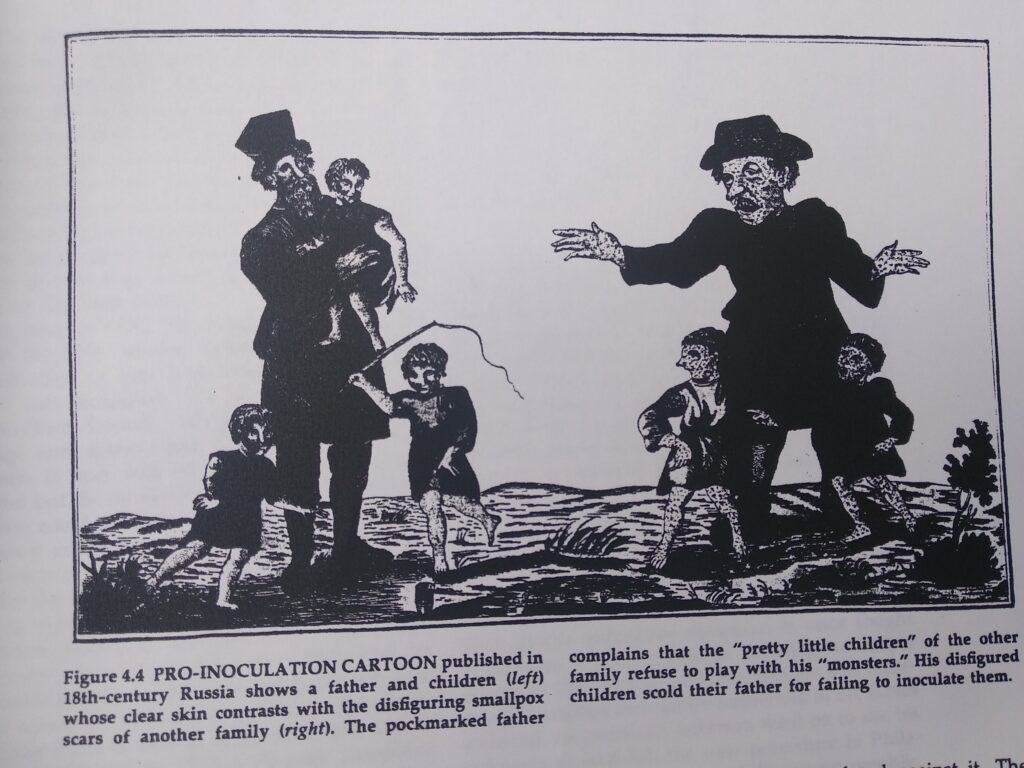

In the eighteenth century some 400,000 Europeans died every year – Between 20 and 60% of all those infected, and over 80% of infected children—died from the disease. Variolation involved introducing the scab of a less virulent form of Smallpox under the skin. After inoculation the disease usually took hold within a week and after another two or more weeks you are likely to recover with only minor scarring from the disease. There was a chance you might die from the inoculation, but given the likelihood of death from exposure to smallpox without inoculation, many took the risk of inoculating their families, servants and others in regular contact within their household.

Initial success in the UK led to Royal approval and massive media interest. Bloodletting, reduced diet, ‘chilling’ and ‘heating’ the feverous body, were often part of the procedure probably leading to many patients being weakened – there were deaths and some smallpox outbreaks that were attributed to the inoculation itself. The procedure was controversial – those who supported, or carried out the procedure were met with skepticism, violence and mocked, and it was not until the early nineteenth century that Edward Jenner’s ‘vaccination’ using cowpox began to replace ‘variolation’ as it did not carry the high risks of permanent scarring and possible death from the inoculation itself.

The house we were staying in, the doors we used, are a living history of a long forgotten series of smallpox epidemics, a disease eradicated nearly fifty years ago. Imagine the fear that might drive people to take a risk to inoculate themselves and their family, and as the fever and pox began to grip, carving your name into a wooden door.

Local records show many relatives of those inoculated at Black Bush House died of Smallpox. It returned every five to ten years as an epidemic throughout the eighteenth century, leading to the establishment of many Pest Houses across the UK. The dates of inoculation carved into the doors are from 1752 to 1758, but there are no other records to show how long the house operated as a pest house.

Although only one major smallpox pandemic hit Europe in the nineteenth century, smallpox persisted. Thanks to massive worldwide research and vaccination programs the last recorded Smallpox death worldwide occured in Birmingham 1978.

So what are the lessons learned from the Smallpox pandemics? Can any comparison be made with COVID-19? Are we really living in unprecedented times?

Smallpox pandemics caused human death and suffering across the world on an unprecedented scale, shaping the world we live in. It was crucial to advances in the field of immunology, the smallpox vaccine being the first widely used vaccine. It took three centuries for knowledge of inoculation to travel from China to the UK, and a further two centuries for it to be perfected and applied systematically in a way that led to smallpox eradication.

Smallpox is the only human disease we have eradicated, taking huge global efforts and cooperation. The World Health Organisation played a vital role in coordinating a world response tracking the disease and supporting all the necessary vaccination programs across the world. Improved global communication and cooperation (at least between Medics) puts us in a much stronger position to deal with any disease.

Pandemics are not unprecedented, even if I’ve not experienced in my lifetime. But if there is anything we should learn from the past it is that cooperation and determined global response works.

Useful reading:

The Speckled Monster: A Historical Tale of Battling Smallpox, Jennifer Lee Caroll (2004)

How 5 of history’s worst pandemics ended, BBC (2020)

Commemorating smallpox eradication – a legacy of hope for COVID-19 and other diseases, WHO(2020)

Smallpox is the only human disease to be eradicated – here’s how the world achieved it, Sophie Ochmann and Hannah Ritchie (2018)

How Smallpox claimed it’s final victim BBC (2018)

History of Smallpox, wikipedia (2013)

Immunization against smallpox before Jenner, William Langer (1976)

The English Inoculator, Jan Ingen-Housz, J. S. Jenkins ( 1996 Soc Med pp.534-537)